The 10 Letters Project.

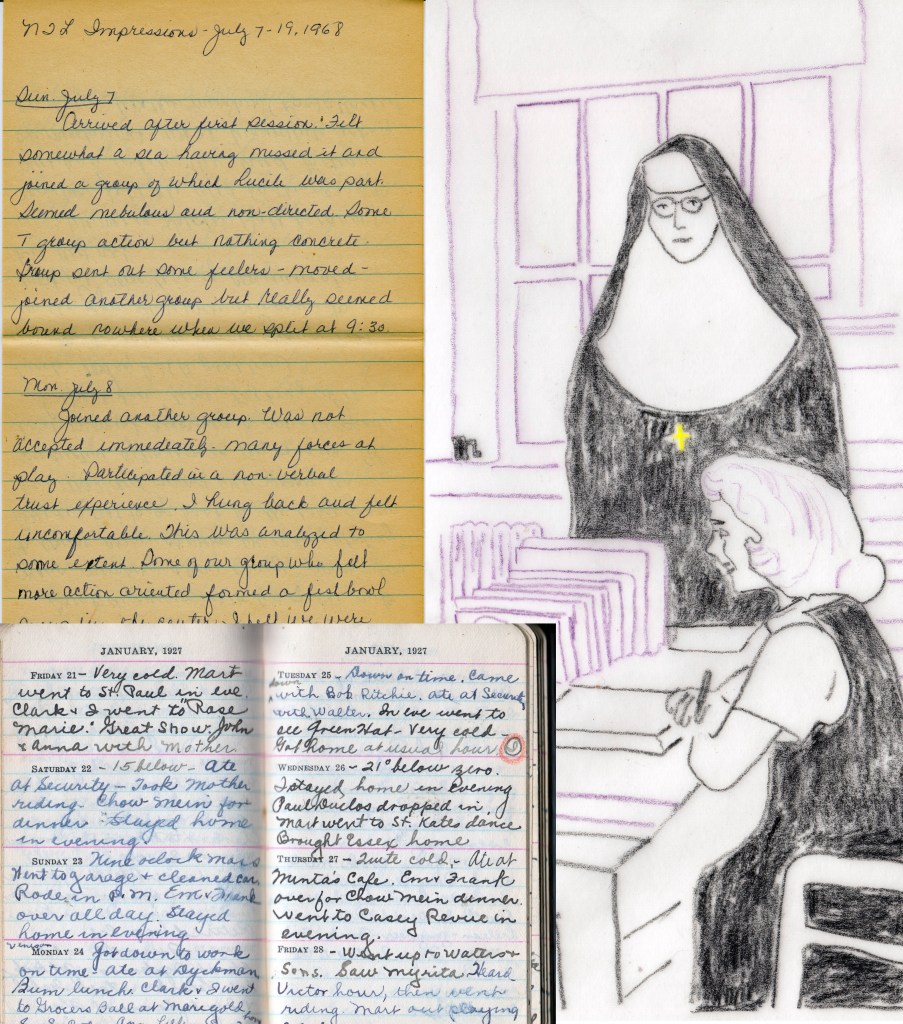

I’ve been going through boxes (many many boxes) of old letters written to and by my mom and to my dad, letters from and to my grandparents. The older ones are yellowing and falling apart. Many were composed on that light blue air mail paper you’d fold up and seal so that it became a self-contained letter and envelope in one.

Some of the letters are interesting (descriptions of trips to Europe or the poetic love my grandfather displayed for my grandmother — even long after they were married!) and others are not that interesting. They were probably never meant to be seen, more like the emails you get from a friend telling you the weather is good and they look forward to hanging out again. And yet here they are, fifty plus years later.

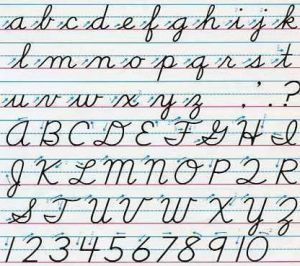

There is something inherently interesting about them just because they are letters. I am not the first person to say this and I won’t be the last, but I miss writing letters and I miss receiving them. Sure, they are dated, their contents composed days or even weeks ago, a lag which now feels almost archaic. But even just one sitting in your mailbox between bills and tactile spam is thrilling. Then there’s how a person’s handwriting can be incredibly revealing (a college boyfriend had incredibly calligraphy which is probably why I didn’t burn them when we broke up).

On a family trip a few years ago my daughter made friends with a woman in her twenties. The woman lived across the country from us so the two of them agreed to write letters, and they did, for more than a year. Mundane, thrilling letters.

It’s probably not a surprise that I like reading collections of letters, primarily of artists and writers. Chekhov’s are great, as are Van Gogh’s, though one of my absolute favorite book is of the letters of children’s book editor Ursula Nordstrom, especially those to her writers, including E.B. White, Margaret Wise Brown and Maurice Sendak.

Recently though, I’ve been getting into those between not-famous people, friends who are just keeping in touch. There’s a fair amount of weather and much mundane life and it reminds me of my family letters, and those I used to send home from camp, which were spectacularly boring, yet must have meant something because they are also included in those boxes.